It’s a sticky August night, and I have a nine dollar beer in one hand and a glitter-glued poster reading “HARRY IS BAE” in the other. My stadium row, seats A-R, consists of three of my similarly outfitted friends, four harried-looking moms, one dad (heavily drinking), and nine girls under the age of fourteen.

I’m twenty-one years old, and I’m at a One Direction concert. I’m questioning my life choices, and I’m not quite sure why.

I’ve convinced myself that I’ve stockpiled enough indie cred to be here—I’ve seen from The Strokes to Kanye to The Avett Brothers, and I had GA passes to Bonnaroo for 48 hours before my sister-in-law told my mom about the acid trip she had there in ’08 and I had to sell my ticket on StubHub. I have every right to one night of bubblegum pop indulgence, but, still, I beg my friends to keep the photos we take off of all forms of social media.

I truly love One Direction—they’ve got catchy songs and an English charm that’s fun and quirky, and, as my sign professes, I think that Harry Styles is a pretty cool guy. I love this band, but, usually, it’s in secret—a guilty pleasure behind closed doors. But why am I so guilty about loving something that brings me such joy?

Why have I been taught that I should hate One Direction?

A quick Google search of “What do you think of 1D” yields a slew of visceral comments. Some of my favorites:

in which Jimmy gets hyperbolic and lazy,

in which Hannah massively dates herself to prove she’s “not like other girls”,

and in which Bee C unknowingly nails it.

We live in an era that devalues teen girls and the things that they enjoy. Gayle Wald, a cultural theorist and Professor of English at The George Washington University, calls it a “high/low hierarchy” of consumer taste based around notions of the changeability, superficiality, and artistic bankruptcy of the material forms that girls’ desires take in popular culture. In a patriarchal society, young girls aren’t meant to be purveyors of culture—they’re seen as too fickle, too shallow, and unable to value things for reasons other than aesthetics.

When teen girls have the social agency to like what they like and influence others to like what they like, however, they become powerful agents of consumerism; their preferences can dictate what sells and what doesn’t and wholly change the landscape of an industry through broad shifting of taste. In terms of the music industry, a mass of screaming girl-fans poses a threat to the established authority—that of the male rock critic, who presides from the likes of Rolling Stone or NME and decries All Those Who Are Not Beck. And when Those Who Are Not Beck challenge NME man’s sovereignty, there are critical backlashes—notably, One Direction had the distinct honor of winning “Worst Band” at the NME awards in 2012, despite that year being the first UK group in history to debut at number one with their first album on the U.S. charts

The landmark achievement—which even legends like The Spice Girls and, yes, The Beatles never attained—was naturally accompanied by huge commercial success, with over five million copies of each of their first three albums sold in three years. A slew of endorsements and branded products followed, from Super Bowl ads with Pespi to two cloying fragrences to a line of scarily inaccurate Barbie dolls, one of which I was gifted for Christmas one year and, ever since, my mom has given a creepy sticky note every time I’ve come home for an academic break. Every. Time.

Such widespread branding leads to cries of sellouts! money machines! chiefly, concerns of inauthenticity. Brought together by the infamous Simon Cowell on the UK hit-show The X-Factor, it’s no surprise that a random assortment of five teenage boys haphazardly thrown together in a pop band on a reality show should need media training, but this is often one of the major bones of contention that One Direction haters are quick to point out—that they’re over-produced by executives, management teams, or Auto-Tune. A hugely orchestrated production team sends signals that heavy marketing and image-pruning are at work.

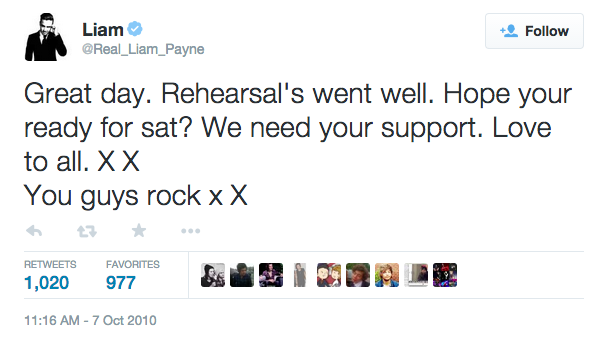

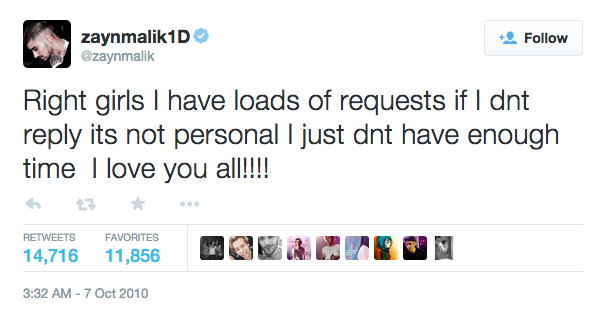

Overproduction and overexposure, however, seems of little concern to young female fans, who again use their (parents’) buying power to stock up on singing toothbrushes and branded makeup (an admittedly odd choice of licensed product for a band who famously croons “Don’t need makeup/to cover up” in their most popular single). And inauthenticity of marketing is trumped by the earnest realism of the band members themselves, who, in the early days of their stardom used personal Twitter accounts and online video diaries to seemingly personally communicate with fans, even if wasn’t in a one-on-one correspondence.

Music videos, too, forged connections between idols and the idolizers, with 2012’s cringe-worthy “Gotta Be You” a perfect example of a tender willingness to appeal to teen girl sensibilities.

The boys moodily travel, in carefully non-coordinated but complimentary outfits, to a dreamy campsite to croon to their jilted loves “Don’t be scared/I ain’t going nowhere”. The video is carefully devoted and crucially nonsexual, providing a place for girls to project their developing desires, conflicts, and insecurities onto an image of nonthreatening masculinity. Girls have a choice, too, in the object of their desire, as each member represents a different kind of figure—Harry’s the cheeky one, Zayn (goodnight, sweet prince) is brooding and mysterious, Liam is dependable, Louis is funny, and Niall’s the cute one. Each role explores a form of romantic instruction that has the potential to be a powerful source of the domestication of female sexual desire, envisioning girls with social agency and the ability to break boys’ hearts—a power that hinges on their ongoing definition as objects of male desire.

One Direction, then, subverts heteronormative paradigms as objects of female desire, which Wald asserts is an important source of their success with fans, who use it to negotiate their own fluid gender and sexual desires. It can be confounded by outsiders as “girlish masculinity” or male femininity, in the deliberately nonsexual but homosocial nature of their presentation—coordinating color schemes, dance moves, even the close physical and emotional contact of members that subsequently constructs male fan desire as homoerotic even as it both shapes and serves the erotic desires of straight girl fans. In straight males, this identification with male femininity or the homosocial aspects of an all-male group provokes anxiety that typically manifests as disdain for the group as a whole and a perpetuation of its alleged queerness (Wald). The obsession of speculative homosexuality within boy bands is not only grossly homophobic, but conflates homophobia (expressed particularly as the fear of male homosexuality) with a misogynist contempt for girls and girls’ pleasure.

And since I hate nothing more than misogyny, I decree: Fuck it. I love One Direction. Their concert was one of the best I’ve ever been to, and I could actually see because everyone, for once in my life, was smaller than me. The quote of the night went to a twelve year old in the parking lot: “I saw their faces…and now I’m a changed woman.” Girl, if that’s what it takes, then so be it. 1D changed me, too.

Works Cited:

Johnston, Maura. “The Enduring Allure of Boy Bands.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 01 Dec. 2012. Web. 28 Apr. 2015.

Moos, Jennifer J. “Boy Bands, Drag Kings, and the Performance of (Queer) Masculinities.” Transposition. Centre De Recherches Sur Les Arts Et Le Langage, 1 Mar. 2013. Web. 28 Apr. 2015.

Wald, Gayle. “‘I Want It That Way’: Teenybopper Music and the Girling of Boy Bands.” Genders Online Journal 35 (2002): 1-21. Web. 28 Apr. 2015.

There is a contradiction between the masses of consumers within the music industry (young girls) and the voices and critiques within the industry (older men) in concerns to One Direction. The boy band has been successful despite it’s lack of critical applause. The mass success of 1D is a result of girls running to by the next album or any product with Harry Styles’ face on it. You describe a formula for 1D’s success as members’ ability to each play a different object of female desire- they are each a different archetype of the boy next door. I don’t really think One Direction is unique in it’s ability to tap into this market. The formula you describes (the boy band archetypes that channel feminine desires) seem to present in a handful of modern boy bands- N*SYNC, Backstreet Boys, and the Jonas Brothers. Do you think 1D criticism is unique or a general (misogynistic and homophobic) critique of the boy band genre?

LikeLike

Unfortunately, I am not a fan of One Direction, but I understand and agree with the pushback that young females receive for supporting this type of musical group. It seems as though despite the fact that the young female population drives the consumer base, the “male rock critic” is the one that holds all the say in the music industry. It is a losing battle though, as it seems that the amount of One Direction fans has not dwindled due to these criticisms. All they can do is insult the band whose popularity has skyrocketed over the last few years. I can understand how it feels to be told that the band you love is terrible, and “overproduced”. I believe that most people are conscious of their taste in music, and are wary of criticism about something that sometimes can say a lot about a person. I was particularly interested, however, when it the entry mentioned how the band empowered females and offered them a non threatening form of masculinity. They, along with numerous boy bands, paint themselves as soft, and caring, and draw girls in with the image that it is the girls who are important. It puts the power in the girls hands, oftentimes songs being about getting your heart broken by a girl.

LikeLike

I thought the Yahoo answers comment from “Hannah” that you posted is a perfect example of people feeling embarrassed to like something that makes them happy. It is so clear when you read a comment like, “I usually think people who sing pop have no talent,” that the person commenting has been told by someone else, who is just as insecure about their own taste in music as the other person, that Pop music is mainstream and, therefore, lame. And she/he has been told that a band is especially lame if it’s girly – or in other words, if it appeals primarily to girls. Furthermore, I think the public should really give teen girls more credit. I mean, teen girls “fangirled” over Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, and the Beatles, and all three artists made a significant impact on the music industry. I also think a similar issue to this is that of why it’s considered totally acceptable to enjoy mindless “guy” movies, but it’s embarrassing to love chick flicks.

LikeLike

It makes me so sad to see how much disrespect girls get from the rest of society. And even from members of their own group with many girls trying to distance themselves from their peers with exclamations that they’re “not like other girls.” Why are girls who wear makeup, watch chick flicks, and fangirl over boy bands so awful? What makes girls who are unfeeling tomboys so superior? Despite all the progress made for women’s status in society, I feel like many people still have this internalized attitude that femininity equals weakness while masculinity equals strength; therefore, anything stereotypically girly gets contaminated with negative attitudes by association while anything stereotypically associated with boys gets a pass. Of course, this is a bit of an oversimplification since it doesn’t apply to everything. However, you can’t really deny the trend’s existence. Boys can scream and cry when their favorite sports team loses, but we criticize girls for doing the same at a One Direction concert. Stereotypically male fields like STEM and business are well-paid and respected while stereotypically female careers like teacher or social worker are undervalued by society. I think people need to analyze and adjust their attitudes towards femininity. Just because it is different from masculinity doesn’t mean that it is inferior.

LikeLike

I thought that this was an exceptionally insightful piece about the gender politics behind the mass teen-girl hysteria behind One Direction. Personally I like a few of their songs, but the normative influence I receive from internet comments and peer feedback for my likes and dislike is distinctively gendered in that – it essentially forces me to adjust my own personal tastes based on the notion of what a stereotypical ‘man’ is supposed to like. If I won’t fit into those stereotypes then – masculinity is somehow at stake. This sort of elitist and misogynistic mindset which you describe fits into this overall picture perfectly as many of the ‘anti-One Direction’ comments are coming from, admittedly jealous males. However, due to the primarily male-dominated wielding of power of judgement in the media today – from the old Rock n’ Roll critics you mentioned to popular media executives of record companies, the warped judgement of the tastes of teen-girls is questioned. However, as you say, if the sheer numbers prove them wrong, they can’t help but be won over – if not for the music – then at least for the money.

LikeLike